By Keith Hayward

Keith is a member of Farnham Humanists committee. He is a retired motor engineer and he currently runs a retail garden nursery in Bisley, Surrey. In this article, he provides a fascinating and in-depth comparison between two Humanist heroes, Charles Darwin and Charles Bradlaugh.

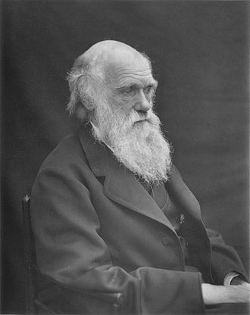

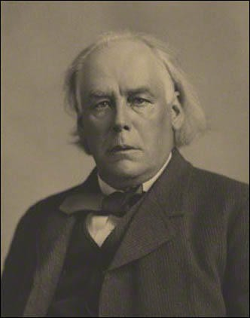

Charles Darwin and Charles Bradlaugh were contemporaries in Victorian Great Britain. They were major figures in the advancement of humanism and secularism. Yet they were from opposite ends of the social spectrum. Darwin was from a well-to-do family in Shrerwsbury, and Bradlaugh was born into poverty in a London slum. Did they know each other? Did they ever meet? Probably not.

| Charles Darwin 1809-1882 | Charles Bradlaugh 1833-1891 | |

|

|

|

| Summary of achievements. | His major lifetime work was discovering and expounding the detail of his theory of evolution by natural selection.

This theory undermined belief in the Old Testamentof the Holy Bible by demonstrating that Genesis is incompatible with science. But he was also active in other areas of natural science, including geology. |

He was an atheist whose lectures and texts undermined belief in the New Testament and the Jesus of the Holy Bible by demonstrating the lack of credibility of the Gospels.

But he was much more than an advocate for atheism. He was also passionate about the need for social change, on such subjects as: • Universal suffrage (votes for all men/women) • Secularism (keeping religion out of politics) • Republicanism (doing away with royalty) • Dispossessing wealthy landowners, • Birth control • Opposition to sabbatarianism (ie those opposing Sunday trading) • Women’s rights • Workers’ rights (trade unions) • Home rule for India • Home rule for Ireland • Teetotalism • Opposition to Socialism (ie public ownership) Success has since been achieved in most of these fields. But he had some failures: • Republicanism • Dispossessing wealthy landowners • Teetotalism |

Did they ever meet? Did they know each other? (Apparently not). |

Darwin refused to be a witness for Bradlaugh in his appeal against conviction in the “Fruits of Philosophy” trial, saying that “artificial checks to the natural rate of human increase are very undesirable and that the use of artificial means to prevent conception would soon destroy chastity and, ultimately, the family. |

In 1877 Bradlaugh (together with Annie Besant) had provocatively invited a fine and imprisonment by re-publishing a banned book (The Fruits Of Philosophy) which advocated birth control. They were convicted and each sentenced to six month’s imprisonment and a fine of £200. Bradlaugh wrote to Darwin asking him to be his witness in his appeal against this conviction. Darwin refused. (Incidentally, Bradlaugh won this appeal and the conviction was quashed). |

Talents |

An experimental scientist, with an aptitude for interpreting detail, and a talent for making perceptive discoveries. He was not much interested in public debate to defend his discoveries. The opposition to Darwin’s discoveries was fierce, and came from organised religion. He left argument to more combative personalities such as T H Huxley, who became known as Darwin’s Bulldog. |

An aptitude for the law, even as an amateur lawyer, that earned the respect of foes and friends alike. He fought many legal cases in his career, sometimes acting alone against some of the best legal brains in the land. He was also a brilliant and moving speaker with a very loud voice, able to attract, control and inspire very large audiences, often 3000 or more (there were no PA systems in those days). A talented writer and publisher. A combative personality, he was also excellent in argument and debate. Tall, around 6ft 2ins with a hefty physique. He was not adverse to using physical violence, particularly against those that disrupted his lectures, but also at times, against the police, and in Parliament. But he was also a pleasant, polite, considerate, and well liked person. |

Childhood |

He was born into a well-to-do family in Shrewsbury. His father (Robert) and grandfather (Erasmus) were both physicians. Erasmus was a freethinker who had expounded ideas similar to evolution and natural selection. His mother Susannah (née) Wedgwood was a member of the wealthy Wedgwood pottery family. |

He was born into poverty. The family lived in a small house in a narrow alley in Hoxton in the East End of London. His daughter Hypatia wrote (in 1896) “The little street has a desperate air of squalor and poverty” His father was a lawyer’s clerk. His mother had been a nursemaid before marriage. |

Education |

He had private schooling as a boarder at Shrewsbury School until university age when his father sent him to Edinburgh University to study medicine, but he abandoned it. His father then sent him to Christ’s College Cambridge with a career as an Anglican parson as the objective. But he had no interest in becoming a vicar. While at university he re-kindled his childhood interest in natural history. |

His schooling ended at 10 years old. Thereafter he was self educated. He became proficient in classical Greek culture, and languages including French, Hebrew, Greek, Latin. |

Initial Employment | In 1831 he joined the HMS Beagle as a self-funded naturalist and gentleman companion to Captain Robert Fitzroy on a five year surveying and mapping voyage of the southern oceans. |

In 1844, at age 11 he was employed as a clerk to a coal merchant. He became a volunteer Sunday-school teacher. He discovered atheism at the age of 16. When the vicar discovered this he was dismissed as a Sunday-schoolteacher, and the vicar also ensured that he lost his paid job, and induced his parents to make him leave home. Destitute, he was given a home by Eliza Sharples, the common-law widow of Richard Carlile (Who had served two prison sentences for atheism). His first public lecture was in 1850, at age 17, on the subject of “The Past, Present and Future of Theology”. But he continued to be dogged by poverty and debt. To get an income and get out of debt he joined the Army. He bought himself out of the army in 1853 at age 20. And took a job as a lawyers errand boy. He was soon promoted, and was handling legal cases on behalf of his employer even though unqualified. |

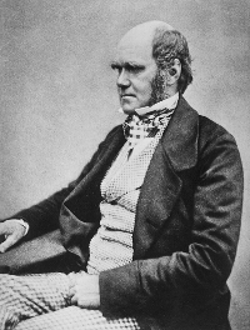

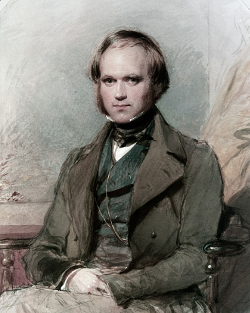

Pictures as young men. |

Painting of a young Charles Darwin Painting of a young Charles Darwin |

Photo of Bradlaugh as a young soldier |

Adult career |

On returning to England he spent many years analysing the data collected on the Beagle voyage, and publishing a number of scientific papers on biology and geology. In 1839 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). In 1858, having not yet published his major work, his theory of evolution by natural selection, he discovered that Alfred Russell Wallace was about to publish a similar theory. Fearing that he would be forestalled, he rushed his book into print. “On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection” was published on 24 November 1859, co-authored with Wallace. His work undermined religious beliefs and caused a storm of controversy that continues to the present day. He was disinclined to become personally involved in arguments, leaving that to more combative personalities. He continued publishing scientific papersand papers and books for the rest of his life. |

While working for his lawyer employer, he was also writing, lecturing and presenting pubic meetings on atheism and other social matters. In order to protect his employer’s reputation he adopted the pseudonym “Iconoclast”, the breaker of images. As a lecturer, he would travel to any part of the UK. He had various lecture tours overseas, including three to the USA. He founded various magazines. Also societies, including The National Secular Society. In 1880 he was elected as Liberal MP for Northampton. He was not allowed to take his seat because as an atheist he was not allowed to take the oath. So there was a by-election which he won. This was followed by two more by-elections, and at each he won and was not allowed to take his seat. Ranged against him were the Conservative Party (particularly Lord Randolph Churchill), and Anglican and Roman Catholic MPs. At the General Election of 1886 he again won, and the matter was becoming an embarrassment to the Government because of the clear over-ruling of the will of the people. So the Speaker ruled that there would be no argument and Bradlaugh could take the oath even though he was an atheist. The howls of protest from Conservative MPs were to no avail. He later became a successful, respected and well liked MP even by those MPs (Including Lord Randolph Churchill) who had previously opposed him taking his seat. |

Family |

In 1839 he married Emma Wedgwood, his cousin. They had 10 children, seven of whom reached maturity. |

In 1855 he married Susannah Lamb Cooper, the daughter of an atheist friend. They had three children, Alice, Hypatia, Charles. Hypatia was named after Hypatia of Alexandria the pagan philosopher, mathematician and scientist who was murdered in year 415 by Christians, but also after Hypatia the daughter of Eliza Sharples, who was his girlfriend for a while. The marriage broke up due to his wife’s alcoholism, although they remained amicable. He despatched his family to live with in-laws at Cocking, near Midhurst. while he lived in a small flat in East London. His son Charles (Charlie) died at age 11 in 1870 of scarlet fever. His wife died aged 45 in 1877. The two daughters then moved to live with their father in London as his assistants. He gave his daughters a good education including at a school in France. He would communicate with his daughters in French. Alice died of typhus and meningitis aged 32. Hypatia died in 1935 aged 77. |

|

| |

Illness and death |

He died at age 73 of heart failure, at Down House, Kent. |

He died at age 58 of Bright’s disease, a progressive and debilitating disease of the kidneys, at his house, St John’s Wood, London. |

Funeral |

At Westminster Abbey. Ironically, a full house Christian service attended by many people who had religious beliefs that had been undermined by his discoveries. |

At Brookwood Cemetery, in unconsecrated ground. A massive event with some 3000 attendees, mainly ordinary people who believed in what he had done and stood for. The ashes of his daughter Hypatia are in the same grave. Nearby are the graves of his wife, his daughter Alice, and his grandson Kenneth.  This photo is dated 17 September 2016, and shows the National Secular Society laying a wreath at the grave to mark the 150 year founding of the NSS by Charles Bradlaugh. The speaker is Terry Sanderson, then President of NSS, now deceased and interred at Brookwood Cemetery near to Bradlaugh. To his right is Barbara Smoker ex-President of the NSS, and to his left is Keith Porteous Wood, the current President.

This photo is dated 17 September 2016, and shows the National Secular Society laying a wreath at the grave to mark the 150 year founding of the NSS by Charles Bradlaugh. The speaker is Terry Sanderson, then President of NSS, now deceased and interred at Brookwood Cemetery near to Bradlaugh. To his right is Barbara Smoker ex-President of the NSS, and to his left is Keith Porteous Wood, the current President. |

Statues. |

Has a statue in the Natural History Museum, and another in Shrewsbury near his old school, and another in the grounds of Christ’s College, Cambridge. |

Has a bust in the House of Commons, fitting for a man who for 6 years was banned from taking his seat the House, and a statue in Northampton where he served as an MP. |

Atheist, Agnostic, or something else. |

He stopped going to church in 1849 following the death of his beloved daughter Annie at age 10. He didn’t believe in organised religion. But also didn’t believe in denying the existence of a God. |

He was strongly atheist, and argued that the word God meant nothing to him. |

Further reading |

Many biographies |

Biographies: 1. The Biography of Charles Bradlaugh by Adolphe Headingley. 1880, 330 pages. Headingley was a personal friend of Bradlaugh. 2. Charles Bradlaugh: His Life and Work. by Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner (his daughter). Published 1894. two volumes. 842 pages. Downloadable online for free, and a good read. 3. President Charles Bradlaugh MP by David Tribe. 1971, 390 pages. 4. Dare To Stand Alone. By Bryan Niblett, Published 2010. 391 pages. A biography of a lawyer, by a lawyer. |